What Is the War on Poverty?

Fifty years ago, on January 8, 1964, President Lyndon Johnson declared "unconditional war" on poverty. We have actual data on these matters which clarify what exactly happened after Johnson's declaration, and the role government programs played. Here's what you need to know.

The term "war on poverty" generally refers to a set of initiatives proposed by Johnson's administration, passed by Congress, and implemented by his Cabinet agencies. As Johnson put it in his 1964 State of the Union address announcing the effort, "Our aim is not only to relieve the symptoms of poverty, but to cure it and, above all, to prevent it."

The effort centered around four pieces of legislation:

• The Social Security Amendments of 1965, which created Medicare and Medicaid and also expanded Social Security benefits for retirees, widows, the disabled and college-aged students, financed by an increase in the payroll tax cap and rates.

• The Food Stamp Act of 1964, which made the food stamps program, then only a pilot, permanent.

• The Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, which established the Job Corps, the VISTA program, the federal work-study program and a number of other initiatives. It also established the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO), the arm of the White House responsible for implementing the war on poverty and which created the Head Start program in the process.

• The Elementary and Secondary Education Act, signed into law in 1965, which established the Title I program subsidizing school districts with a large share of impoverished students, among other provisions. ESEA has since been reauthorized, most recently in the No Child Left Behind Act.

Many of the war on poverty's programs — like Medicaid, Medicare, food stamps, Head Start, Job Corps, VISTA and Title I — are still in place today. The Nixon administration largely dismantled the OEO, distributing its functions to a variety of other federal agencies, and eventually the office was renamed in 1975 and then shuttered for good in 1981.

Did it reduce poverty, actually?

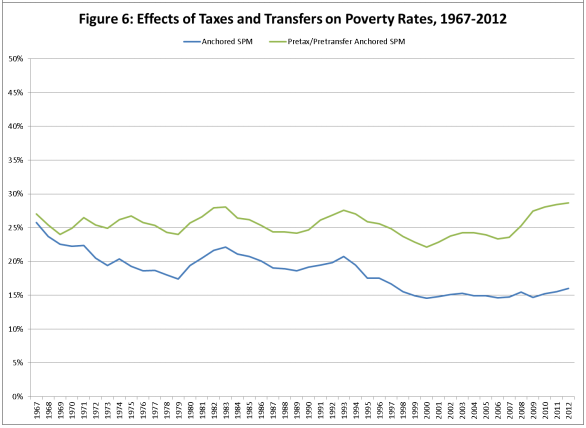

It did. A recent study from economists at Columbia broke down changes in poverty before and after the government gets involved in the form of taxes and transfers, and found that, when you take government intervention into account, poverty is down considerably from 1967 to 2012, from 26 percent to 16 percent:

The term "war on poverty" generally refers to a set of initiatives proposed by Johnson's administration, passed by Congress, and implemented by his Cabinet agencies. As Johnson put it in his 1964 State of the Union address announcing the effort, "Our aim is not only to relieve the symptoms of poverty, but to cure it and, above all, to prevent it."

The effort centered around four pieces of legislation:

• The Social Security Amendments of 1965, which created Medicare and Medicaid and also expanded Social Security benefits for retirees, widows, the disabled and college-aged students, financed by an increase in the payroll tax cap and rates.

• The Food Stamp Act of 1964, which made the food stamps program, then only a pilot, permanent.

• The Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, which established the Job Corps, the VISTA program, the federal work-study program and a number of other initiatives. It also established the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO), the arm of the White House responsible for implementing the war on poverty and which created the Head Start program in the process.

• The Elementary and Secondary Education Act, signed into law in 1965, which established the Title I program subsidizing school districts with a large share of impoverished students, among other provisions. ESEA has since been reauthorized, most recently in the No Child Left Behind Act.

Many of the war on poverty's programs — like Medicaid, Medicare, food stamps, Head Start, Job Corps, VISTA and Title I — are still in place today. The Nixon administration largely dismantled the OEO, distributing its functions to a variety of other federal agencies, and eventually the office was renamed in 1975 and then shuttered for good in 1981.

Did it reduce poverty, actually?

It did. A recent study from economists at Columbia broke down changes in poverty before and after the government gets involved in the form of taxes and transfers, and found that, when you take government intervention into account, poverty is down considerably from 1967 to 2012, from 26 percent to 16 percent:

While that doesn't allow us to see how poverty changed between the start of the war in 1964 and the start of the data in 1967, the most noticeable trend here is that the gap between before-government and after-government poverty just keeps growing. In fact, without government programs, poverty would have actually increased over the period in question. Government action is literally the only reason we have less poverty in 2012 than we did in 1967.

What's more, we can directly attribute this to programs created or expanded during the war on poverty. In 2012, food stamps (since renamed Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP) alone kept 4 million people out of poverty:

Why don't people think it reduced poverty?

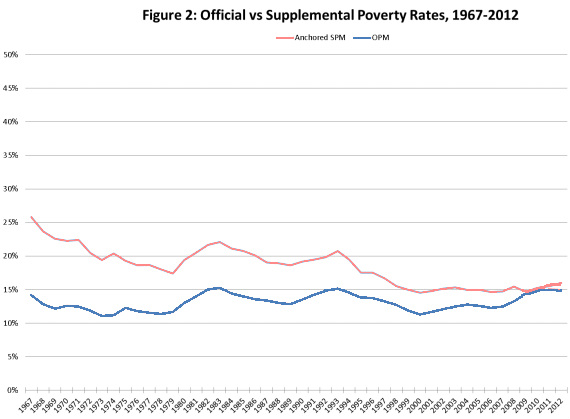

Largely because people rely on the official poverty rate, which is a horrendously flawed measure, which excludes income received from major anti-poverty programs like food stamps or the EITC. It also fails to take into account expenses such as child care and out-of-pocket medical spending. If you look at the traditional rate — which, I'm not even kidding, is based on the affordability of food for a family of three in 1963/4, with no adjustments except for inflation since then — it looks like poverty has stagnated rather than fallen.

What's more, we can directly attribute this to programs created or expanded during the war on poverty. In 2012, food stamps (since renamed Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP) alone kept 4 million people out of poverty:

Why don't people think it reduced poverty?

Largely because people rely on the official poverty rate, which is a horrendously flawed measure, which excludes income received from major anti-poverty programs like food stamps or the EITC. It also fails to take into account expenses such as child care and out-of-pocket medical spending. If you look at the traditional rate — which, I'm not even kidding, is based on the affordability of food for a family of three in 1963/4, with no adjustments except for inflation since then — it looks like poverty has stagnated rather than fallen.

So when you read, say, the Cato Institute's Michael Tanner writing things like, "the poverty rate has remained relatively constant since 1965, despite rising welfare spending," keep in mind that that statistic is completely meaningless in this context. The relevant measure is the supplemental poverty measure which, as mentioned above, fell following the start of the war on poverty.

What more could we be doing now to fight poverty?

So many things! We could expand existing working anti-poverty programs like Social Security, the Earned Income Tax Credit, the child tax credit and food stamps, or at least reverse recent cuts to the latter. We could, similarly, cut taxes on the working poor, perhaps by exempting the first $10,000 or so of a worker's earnings from payroll taxes, or by cutting down on the extremely high effective marginal tax rates which poor Americans face. We could adopt a still more dramatic transfer regime, such as a basic income or low-income wage subsidies. We could be investing in education, such as by scaling up successful pre-K pilots such as the Perry or Abecedarian experiments, or by expanding high-performing charter schools and having traditional public schools adopt their approaches. We could raise the minimum wage, which all researchers find reduces poverty.

Source: Everything you need to know about the war on poverty

By Dylan Matthews January 8, 2014, The Washington Post

What more could we be doing now to fight poverty?

So many things! We could expand existing working anti-poverty programs like Social Security, the Earned Income Tax Credit, the child tax credit and food stamps, or at least reverse recent cuts to the latter. We could, similarly, cut taxes on the working poor, perhaps by exempting the first $10,000 or so of a worker's earnings from payroll taxes, or by cutting down on the extremely high effective marginal tax rates which poor Americans face. We could adopt a still more dramatic transfer regime, such as a basic income or low-income wage subsidies. We could be investing in education, such as by scaling up successful pre-K pilots such as the Perry or Abecedarian experiments, or by expanding high-performing charter schools and having traditional public schools adopt their approaches. We could raise the minimum wage, which all researchers find reduces poverty.

Source: Everything you need to know about the war on poverty

By Dylan Matthews January 8, 2014, The Washington Post